Where to start in the whole of Japanese literature? Where better than with a book whose title is a matter of dispute, and which is the work of a haiku master?

奥のほそ道(おくのほそみち) (Oku no Hosomichi) by 松尾芭蕉(まつおばしょう) (Matsuo Bashō) is in the form of a travelogue interspersed with poems written at each place where Bashō and his travelling companion Sora stayed. It starts with the wonderful sentence:

月日は百代の過客にして行かふ年も又旅人也。

which Donald Keene translates as:

The months and days are the travellers of eternity. The years that come and go are also voyagers.

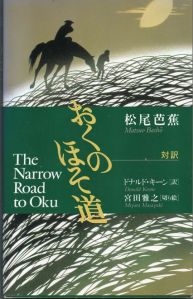

When I first came across this, I was only beginning to learn Japanese, but I was struck by what an evocative sentence this was, even though it was made up at least partly from simple kanji that even I, as a beginner, could already read – 月 (moon/month), 日 (sun/day), 百 (hundred), 行 (go), 年 (year) and 人 (person) are among the first characters to be taught in most textbooks (with the exception of Heisig – of whom more on another occasion – who starts off with the sun and goes onto crystals and choirs!). Of course, being able to recognise a few kanji and being able to read a text in seventeenth-century Japanese are two quite different things, and a good translation is definitely needed to be able to enjoy it. The version I have is the Kodansha International bilingual edition with English translation by Donald Keene and illustrations by Miyata Masayuki (ISBN 4770020284). For those who are able to read it, there is an online version of the text provided by the University of Virginia here.

So how to translate the title into English? The variants I have come across so far are “The Narrow Road to the Deep North” (probably the best known), “The Narrow Road to Oku” (the Keene translation), “Narrow Road to the Interior”, “The Narrow Road Through the Provinces” and “Back Roads to Far Towns”. The “narrow road” part appears relatively uncontroversial – 細い(ほそい) (hosoi) means ‘narrow’ and 道(みち) (michi) is a road or path – but 奥(おく) (oku) has a range of meanings and nuances that are not easily covered by a single English word. It is translated as ‘interior’ or ‘heart’ (in the sense of the centre of something, rather than the organ) or ‘inner recesses’ (Keene) but the character was also part of the name of the former province of Japan, variously known as 陸奥国(むつのくに) (Mutsu no kuni), 奥州(おうしゅう) (Ōshū) or Michinoku 陸奥(みちのく) or 道奥(みちのく), to which Bashō travelled, and which corresponds to the modern Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate and Aomori Prefectures and part of Akita Prefecture. This is the part of Japan where I first made my home in 2006 and the part that was, more recently, devastated by the earthquake and tsunami of 2011. Apart from large cities such as Sendai, the area is still a somewhat rural part of Japan, and certainly far from the image that many people have of a high-tech world of robots and anime characters. Many of the towns that Bashō visited have a monument to the fact, such as a stone inscribed with one of his haiku, and some have created an entire tourist industry around his visit – notably Matsushima, which is more famous for a poem that Bashō may or may not have composed

matsushima ya

aa matsushima ya

matsushima yaMatsushima!

Ah, Matsushima!

Matsushima!

than for the one that Sora actually did compose:

matsushima ya

tsuru ni mi o kare

hototogisuMatsushima!

Borrow your plumes from the crane

O nightingales (trans: Keene)

possibly because it is difficult to understand at this distance in time what the significance of the cranes and nightingales in Sora’s poem are. (Any haiku experts who can shed some light on this, please do leave a comment!)

After visiting Matsushima and other coastal towns, Bashō went deep into the interior (奥) mountain country, the realm of the ascetic Shugendō sect of Shintō . Those who have lived in Japan will know that the majority of towns and cities are along coastal plains and there are large mountainous areas in the interior part of the country that are very sparsely populated, if anyone lives there at all – some indication of this can be seen on the ‘population’ map on this page. The ‘interior’ is therefore not just the ‘back of beyond’ or ‘inland regions’ but a mysterious place, far from the bustling, worldly life of Edo (modern Tokyo). Perhaps there is even a sense that Bashō is journeying into his own interior.

From one of my conversations with Nobuyuki Yuasa, author of Narrow Road to the Deep North:

Nobuyuki Yuasa first read Basho’s Oku no Hosomichi, or Narrow Road to the Deep North, when he was a high school student. This was his first introduction to the world of haiku: Yuasa says, “I was immediately captivated by it. Soon I began to read works of other poets, such as Buson and Issa. Modern haiku after the Meiji Restoration, however, did not interest me so much. In college, I specialized in English literature and studied the works of T. S. Eliot and John Donne. When I returned to Japan after obtaining an M.A. from Berkeley, I began to translate works of classical haiku poets. In 1967, The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches was published by Penguin Classics.”

He also translated: The Year of My Life: Issa’s Oraga Haru, and The Zen Poems of Ryokan.

LikeLike

In addition, Dorothy Britton who wrote A Haiku Journey: Narrow Road to a Far Province was a friend of mine:

I shared with Professor Yuasa that Dorothy Britton, who was a neighbor of mine in Hayama had also translated Basho’s famous haibun as A Haiku Journey: Basho’s Narrow Road to the Far Providence(1974) In March of 2002, I was proud to introduce them in Kamakura. Dorothy Britton, Lady Bouchier was born in Yokohama. Her father was British and her mother American. Britton is known as a composer and translator of well-known books as Totto-chan, the Little Girl at the Window, and The Girl with the White Flag besides A Haiku Journey. Britton was always cheerful and friendly. I remember that she sent me a postcard when I returned to the U.S., and asked how I was adapting. In the spring of 2015, Britton passed away.

LikeLike

Thank you for this fascinating information, SterbaPoet! I’d love to read these other two translations. I just did a little search and found this recording of Professor Yuasa lecturing on Basho and the haiku tradition: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/poetrycenter/bundles/226790

LikeLike